How do items in a museum come to be there? Who owns cultural assets? And last but not least: should we revise the whole concept of the museum as an institution? If so, how? I am faced with all these questions on a day-to-day basis in the course of my voluntary work in provenance research. Since February 2023, I have been at Landesmuseum Hannover – a truly historic place in which to pursue such work: in order to ensure that the “treasures of knowledge gained by mankind do not [dwell] within the limited reaches of the brains of individuals alone” (Georg Philip Holscher, 1850), civic associations founded the Hannoversche Museum für Kunst und Wissenschaft (“Hannover Museum for Art and Science”) in 1852. Today, 171 years and two name changes later, the Landesmuseum, true to its epithet “WeltenMuseum” (“museum of worlds”), accompanies visitors on their journeys through “natural worlds”, “art worlds” and “human worlds”.

The Provenance Research Department at Landesmuseum Hannover, headed by Dr Claudia Andratschke, has been investigating the museum’s holdings since 2008. While the focus was initially on Nazi-looted cultural property, research into collections from “colonial contexts” was added in 2013. I have therefore had the opportunity to familiarise myself with both areas. Through the Netzwerk für Provenienzforschung in Niedersachsen“ (“Network for Provenance Research in Lower Saxony”) based at the Landesmuseum, the doors of numerous other museums are open to me where colleagues are likewise engaged in shedding light on the provenance of collections.

When I first heard about “provenance research” in my history studies in 2017, I could hardly begin to imagine the diversity of this subject area: on a guided tour seminar on “Göttingen University under National Socialism”, it was my task to introduce my fellow students to “Nazi looting and looted property at the Historical State and University Library”. As fleeting as this first contact was, it motivated me to get an initial taste of the field of provenance research in 2019 by taking an internship at Landesmuseum Hannover. There was a lot going on at the time: the PAESE project was about to get started in which the five largest ethnographic collections in Lower Saxony critically examined their non-European holdings and sought to engage in dialogue with researchers in the so-called countries of origin. As a result, I got to familiarise with myself with my current workplace in the midst of turbulent preparations for the arrival of scholars from Cameroon, Tanzania, Namibia, Papua New Guinea and Germany.

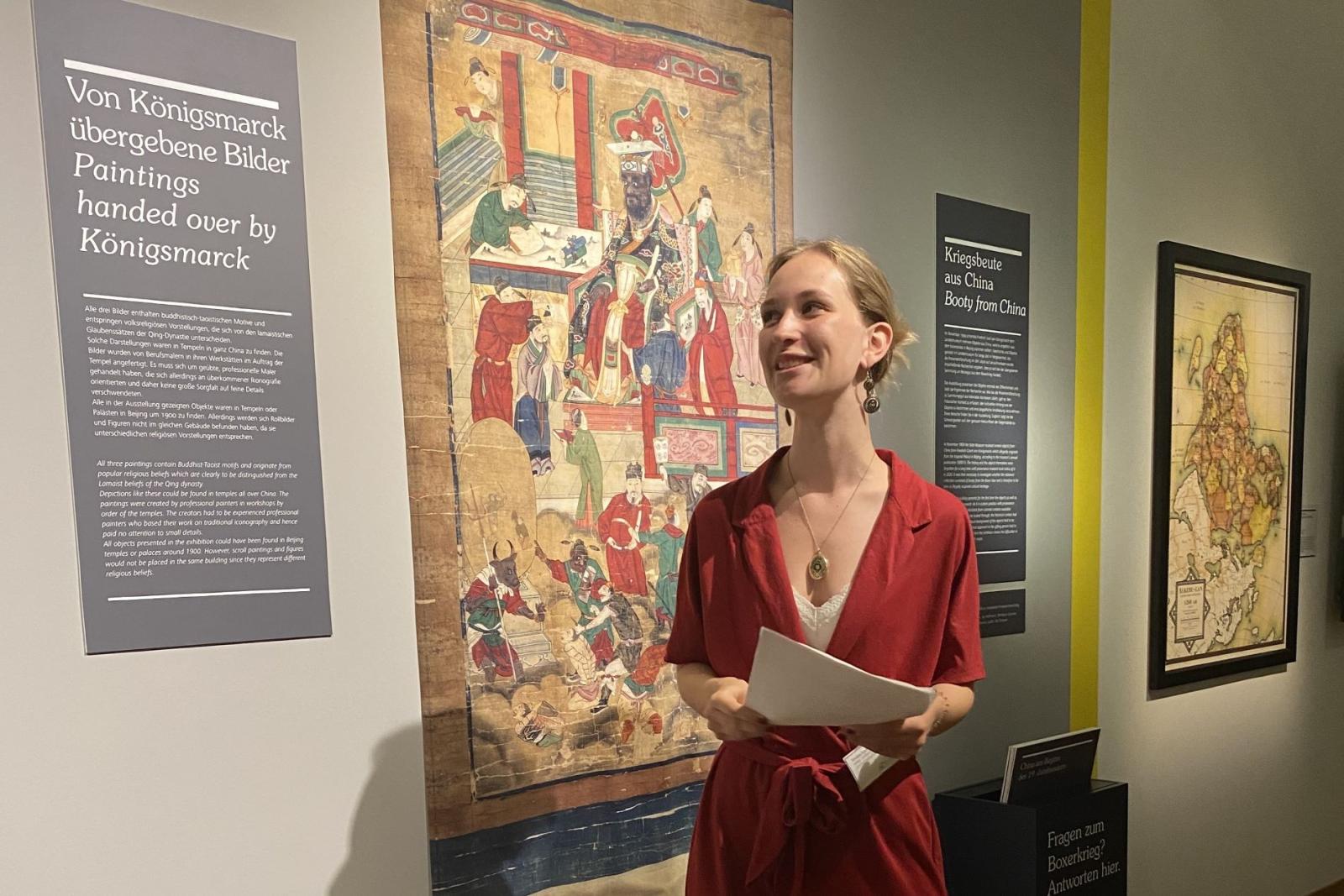

Works by old and new masters on the grids of the sliding frame systems in the art depots, masks, weapons and all kinds of everyday objects behind the glass panes of the ethnological display depot: beyond the exhibition areas, there are entire “worlds” slumbering that are completely detached from their origins. Compared to the size of the depots, the permanent exhibition can at best be described as the tip of the iceberg. I am still moved today by the fact that every single object has its own story to tell and, more importantly still, has links to real individuals. It is true that in my studies I dealt with the crimes of National Socialism and closely studied the history of colonialism and racism. But when I walk through the depots and encounter the sheer mass of objects from all over the world face to face, I become particularly aware of the consequences of these historical events: in the museum’s collections, history is transported into the present – and for me, that means consistently asking new questions. What is rightfully in our possession? What is not?

Provenance research in a museum with multiple departments requires a 360° view: not only a painting might be suspicious, but also a turtle shell from Indonesia or a stone puma from Bolivia. A wide variety of cases have already crossed my desk. Of course, the Landesmuseum has not been unaffected by external developments. Only recently there has been a renewed focus on the Cameroonian collections, parts of which were already processed in connection with the PAESE project; this came about as a result of the publication by Benédicte Savoy and Albert Gouaffo entitled Atlas der Abwesenheit. Kameruns Kulturerbe in Deutschland. Due to this increased interest in over 40,000 Cameroonian objects in German museums (most of which were acquired during the German colonial period), it is currently my task to further examine the provenance of the relevant holdings at the Landesmuseum.

So how can we reconceive museums as institutions? There is no universal answer to this question of course. But museums as institutions do have to position themselves in a world where right-wing and racist ideologies are consistently gaining more ground. In order to do this, it is first important to acknowledge our own past, subject it to critical appraisal and make it transparent: museums actively participated in the confiscation of cultural assets and profited from historical injustice under National Socialism and colonialism, and the suffering this caused is still manifested in museum collections to this day. The fact that there are voices that play down this past or even call for it to be forgotten means it is all the more important for us to take a critical look at the origins of collections. Though the once postulated prerogative of the museum in interpreting history is to be fundamentally questioned, I do believe that museums should make the most of their status to keep history and stories of the past alive, include as many perspectives as possible, and gear future action towards these diverse perspectives. In this sense, it is a worthwhile undertaking to pursue provenance research and continue to investigate collections.

Louisa Hartmann is a research volunteer at Landesmuseum Hannover/Netzwerk für Provenienzforschung in Niedersachsen.