The boom in the use of the term “provenance research” over the last ten years can be regarded as a remarkable phenomenon. My approach to research about provenance research is to examine the relevant historical, social and cultural dimensions of this phenomenon. When I started to look into the topic, the first questions that came to my mind were: has provenance research always existed? And if so, what was its focus before?

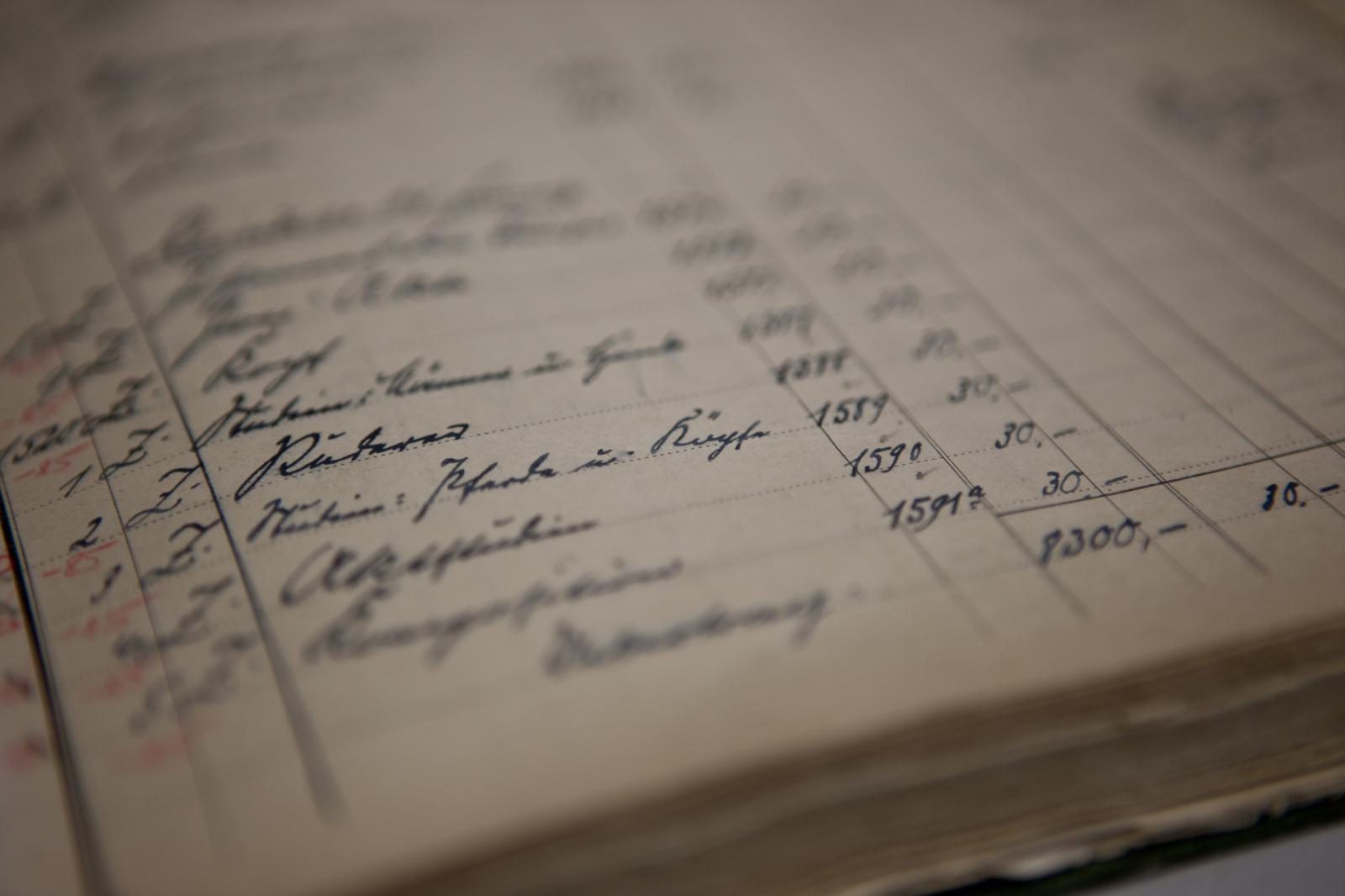

According to the website of the German Lost Art Foundation in Magdeburg, the beginnings of the Foundation – and therefore of state-organised provenance research – lie in the “Koordinierungsstelle der Länder für die Rückführung von Kulturgütern” (“Coordination Office of the Federal States for the Return of Cultural Property”) in Bremen, which was founded in 1994. At that time, however, virtually no one used the term “provenance research” when referring to activities that would be referred to as such today. In the files on the establishment of the Koordinierungsstelle (Coordination Office) and the activities it pursued from 1994 onwards, terms such as “art detectives” and “hunters of lost treasures” appear, as well as the neutral term “experts”. Even prominent provenance researchers in those early days would not have described themselves as such at that time. Regarding the focus of the Koordnierungsstelle (Coordination Office), we can say the following: at that time, the Office dealt almost exclusively with art and cultural objects that had been art and cultural institutions of the German Reich had lost during the Second World War – so-called looted art. In particular, the focus was on the Soviet occupation and the so-called “trophy brigades”. After the disintegration of the Soviet Union, those federal states which were particularly affected saw a chance to regain possession of these items. The federal government did not remain idle either, however, and two institutions were founded in parallel at the beginning of the 1990s: the Dokumentationsstelle (Documentation Centre) of the Cultural Branch of the Federal Ministry of the Interior, and the Koordinierungsstelle der Länder (Coordination Office of the Federal States) in Bremen, which was established at the initiative of some of the federal states.

In reconstructing these developments, I find it remarkable that the files of the Koordinierungsstelle (Coordination Office) from 1994 contain virtually no mention of confiscation from private individuals due to Nazi persecution – the area that is considered the main task of provenance research today. It was not until the end of the 1990s (in other words 50 years after the end of the Holocaust) that this topic shifted increasingly onto the political and public agenda – above all through the impact of the 1998 Washington Conference initiated by the US Holocaust Memorial Museum and the US State Department. This gradually led to an expansion of the remit of the Coordination Office, which has since moved to Magdeburg, and also resulted in the founding of the Arbeitsstelle für Provenienzforschung (Bureau for Provenance Research) at the Institute für Museumsforschung (Institute for Museum Research) of the Staatliche Museen zu Berlin (National Museums in Berlin) in 2008. At that time there were very few people thinking about other focus areas of provenance research that are relevant now, such as the Soviet occupation zone/GDR and colonialism. The whole issue of remembrance and remembrance policy is a key factor in understanding this selective focus in the development of state-organised provenance research. In terms of the context of National Socialism, I assume the following: based on an initial assessment, there is an interrelation in the Federal Republic of Germany between the societal negotiation of memory, remembrance policy and the institutionalisation of provenance research. A parallel example here is the compensation of forced labourers, another consequence of National Socialism. Here again the year 1998 was a turning point. In that year, the parliamentary groups in the Bundestag agreed to establish a foundation called Erinnerung, Verantwortung und Zukunft (“Remembrance, Responsibility and Future”) to compensate for forced labour involving the German private sector (again, more than 50 years after the end of the Holocaust). One of the main factors in this case was a wave of lawsuits from the USA, along with negative international and national reporting.

If we look back at state-organised provenance research in the period after 1998, further parallels can be drawn in connection with a well-known example: in 2013, in connection with the so-called Gurlitt affair, an article in the magazine Focus brought the story of a partially incriminated (private) art collection to the attention of the national and international public. Government agencies, especially the Federal Government Commissioner for Culture and the Media, were initially caught off guard – not least by the international response: immediately after publication of the Focus article, the Holocaust commissioners of Israel, the USA and the United Kingdom contacted the German authorities and demanded clarification. Political and media pressure, both international and national, was an important factor that forced the Federal Republic to take action. This ultimately also led to the establishment of the German Lost Art Foundation, this time not primarily under the control of the federal states as before but of the Federal Government Commissioner for Culture and the Media.

Among other things, the reactions on the part of the federal government described here served to avert/prevent national and international criticism of the inadequate reappraisal of National Socialism. This was accompanied by an ongoing centralisation of cultural and remembrance policy issues at the federal level. Since 1990, “the mode known as ‘culture of remembrance’” (Astrid Messerschmidt) has developed into an official state-constituting element in the self-image and international representation of the Federal Republic of Germany. The following question arises: as its institutionalisation progresses, is state-organised provenance research becoming part of the “fundamental cultural endowment of the Federal Republic” (Volkhard Knigge), and if so, and what are the consequences?

In research into provenance research, it is important to answer these questions not only in relation to the context of National Socialism and the context of “looted art”, but also for the other two major departments of the German Lost Art Foundation, namely the Soviet occupation zone/GDR and colonial contexts, as well as considering how these relate to one another.