In 2006, a poster campaign was organised by the Viennese advertising company Gewista to bid farewell to the painting Adele Bloch-Bauer I (1907) by the artist Gustav Klimt, which was considered a “national treasure”. Seized from its rightful owners in 1938 as a result of Nazi persecution, the painting was returned 68 years later by the Österreichische Galerie Belvedere to the heiress Maria Altmann, a resident of the USA. The illuminated posters installed in Vienna’s city centre showed a section of Klimt’s portrait of a woman, with the words “CIAO ADELE” in bold letters above it.

Posters were also put up to provocative effect in public places in 2021, this time in Dresden. Initiated by the Dresden State Art Collections, the poster campaign by artist Emeka Ogboh bearing the words “VERMISST IN BENIN” (“Missing in Benin”) drew attention to the bronze sculptures that have been in the possession of European museums for more than 120 years – in this particular case in the State Ethnographic Collections of Saxony. Since their violent appropriation by British colonial troops in 1897, the loss of these artefacts has created a void in their place of origin, namely the former Kingdom of Benin in present-day Nigeria.

The posters in Vienna and Dresden took the debate on looted property and restitution out of the institutional context of museums and into the urban space, thereby promoting public awareness of the issues and opening up a dialogue in a broader social setting. But how do museums themselves deal with cultural assets whose provenance bears witness to the violence and crimes committed during the eras of National Socialism and colonial rule and whose removal today or in the future is marked by an empty space in the collection?

The cases outlined here highlight the absence of items after restitution and the question of how to deal with this issue – and such cases are by no means uncommon. In fact, conscious engagement with such absences has increased as a result of heightened interest in provenance research. If what Foreign Minister Annalena Baerbock said proves to be true that the signing of the political statement on the return of the Benin bronzes on 1 July 2022 is only the beginning, the number of empty spaces in German collections will increase in the future and the question of how to deal with this issue will become increasingly relevant. In the context of Nazi-looted property, too, the gaps left as a result of restitutions have long ceased to be isolated instances. In addition there are the gaps caused by the National Socialists’ “Degenerate Art” campaign and by losses and transfers that occurred as a result of the Second World War. There are fundamental differences between these constellations, however, and this is precisely the challenge that curators face today: how can a historically complex set of circumstances be exhibited in a museum when the item concerned is absent? And given that this very absence is key to the narrative of the exhibition, how is it possible to showcase physical non-presence as a repository of remembrance, and what message can this convey?

In the rooms of Galerie Belvedere in Vienna, the empty space left by the restituted Klimt painting was filled with another exhibit. In the Dresden State Art Collections, by contrast, the decision was made to highlight the presence/absence of the Benin bronzes in the exhibition space by making this a deliberate theme: after the objects from the Benin collection had been moved to the depot, works from the series At the Threshold – also developed by Emeka Ogboh – were interposed in the Dresden and Leipzig collection presentations so as to raise awareness of the debate.

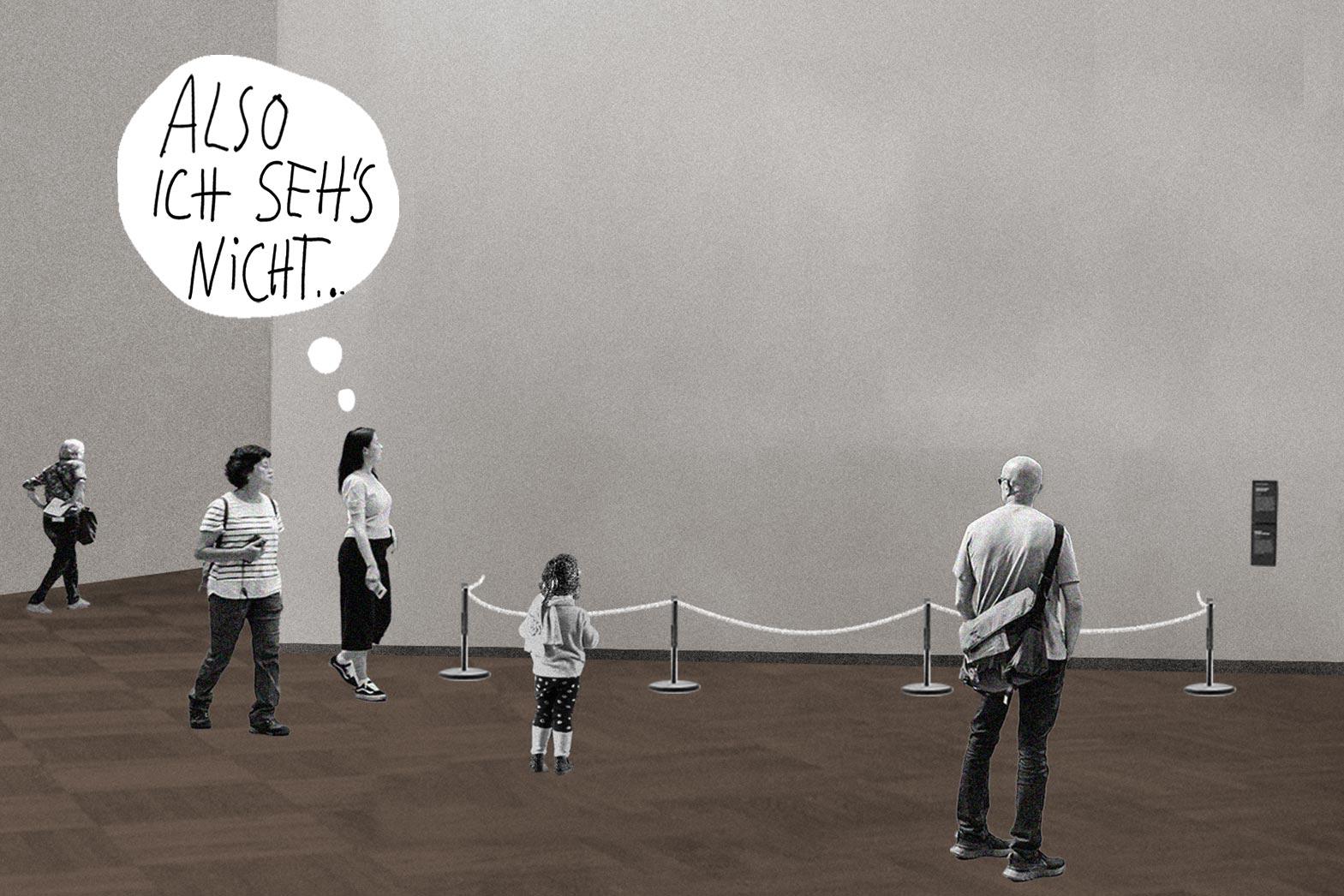

Other contemporary artists such as Lisl Ponger (Horror Vacui, 2008), Simon Schubert (Das Brandzimmer, 2018) and Christian Jankowski (Leihgabe, 2017) take up the theme of absence, too: works are created that do not replace what is absent but reflect on the absence and build a bridge between the past and the present. Other curatorial options including displaying an empty frame to indicate a missing painting (Städel Museum Frankfurt/M. 2019/20), putting up a square wall marker in place of a drawing (Dresden State Art Collections, Residenzschloss, 2018/19), and using an empty display case to act as a reference to an absent object (MARKK Hamburg, 2023). In addition to reproductions, technical aids are also frequently used. The spectrum here includes a light projection at Hamburger Kunsthalle (2013), light boxes at Kunststammlung Gera (2011) and a VR installation at Kunstmuseum Moritzburg (2019).

Yet presentation techniques alone are not sufficient to convey the diverse and often complex background to a missing item. Other forms of communication have a key role to play here, too, providing context, identification and explanation. Features such as wall texts, audio guides and media stations can be used to indicate the whereabouts of missing items, convey ambiguities and gaps in knowledge, or provide insights into areas of museum work which normally remain hidden from the public.

Museums are defined by their collections, and every gap in a collection is a reference to history – not least to the history of the institution itself. As a place that conveys socially relevant content and promotes historical education, a museum is subject to constant change, as is the practice of exhibiting. More than anything else, the presentation of gaps offers the opportunity to stimulate discussion about responsibility, remembrance, restitution and the role of cultural property in our society. Perhaps the future will reveal other ways in which absence and its testimony can be integrated and visualised as a repository of memory in exhibitions so that the latter can act as an interface between past, present and future.

The author is a doctoral student at the Technical University of Dresden and a Fellow of the Hans Böckler Foundation. She conducts research into the absence of cultural artefacts in today’s collections as a result of colonialism and National Socialism and pursues the question of how different types of absence can be successfully presented in exhibitions.