The use of photographs as evidence of anti-Semitic spoliation during the Nazi era is not the most widely discussed aspect of Holocaust litigation. This brief article does not pretend to fill this gap, but merely to provide a starting point for further analysis. More specifically, we will look at historical photographs as pieces of evidence in the restitution of cultural property in contemporary France. Although Einsatzstab Reichsleiter Rosenberg ("ERR") practice in photographing looted cultural property is well known, the issue at stake is not an easy one: how does photography fit into the legal landscape of property litigation existing in the twenty-first century, in order to prove facts or acts committed during the Nazi era (1933-1945)? Time is the enemy of evidence; and in the case of the wrongs of history, it is fundamental, albeit complicated to produce.

As such, pictures are not always present in the disputes. In the case of the restitution of Gustav Klimt's Rosier sous les arbres, the information for the press by the French Ministère de la Culture only refers to photographs of the private home of Viktor and Paula Zuckerkandl to highlight that the painting is still in its original frame (Dossier de presse, p. 12). However, a photograph of the artwork with Nora Stiamsy exists, and is used to illustrate the case (see picture 1). In the restitution of Carrefour à Sannois (attributed to Maurice Utrillo) to Georges Bernheim's heirs, photographs are only mentioned alongside a list in order to state that the work had been identified as looted by the ERR (opinion of the CE 07 October 2021 p. 5, National Assembly report referring to it p. 47, Senate report p. 7). For the restitution of The Penitent Magdalene (considered to be the work of Adrian Van der Werff) to the heirs of Lionel Hauser, there was no use of photographic evidence. Only a mention, "photo", suggests that the work had been declared to the French Commission de récupération artistique after the war (jugement du 27 janvier 2023, p. 12). The case that made the most use of photographs as evidence was that of the return of three paintings by the painter André Derain to the heirs of the French collector René Gimpel. We are therefore going to take a closer look at this case and the ways in which photographs are used. The first two paintings were in the Musée d'Art Moderne in Troyes: Paysage à Cassis (or Vue de Cassis, 1907) and La Chapelle-sous-Crécy (or Le Moulin, 1910). The third, Pinède, Cassis (1907), is on display at the Musée Cantini in Marseille.

In this French court case photographs played a crucial role both at the trial (Tribunal de grande instance de Paris – “TGI” – 2019), and on appeal (Cour d'appel de Paris – “CA Paris” – 2020). The challenge for the Gimpel heirs was to demonstrate to the civil judges that the three paintings in French museums had been looted from René Gimpel as a result of the anti-Semitic legislation in force in France during the Second World War. It should be noted that the legal grounds on which the case was based, the restitution order (ordonnance) of 21 April 1945, does not provide any means of proof. In these law cases, images were used to identify the artworks. This is not without recalling the links between photography and truth (Mnookin, 1998), or the debates between historical truth and judicial truth. But isn't the question not whether it is true, but "about what does this photograph tell the truth" (Becker, 2007)? Ultimately, this is what the judges are answering in their examination of the evidence: what does the photograph tell us?

At trial (TGI, 2019), the heirs provided the catalogue of the sale (of the Kahnweiler collection) that had taken place in 1921, and at which Gimpel had bought the three paintings. It contained some information, but the judges noted that there were no photographs of the claimed paintings, which made them impossible to identify.

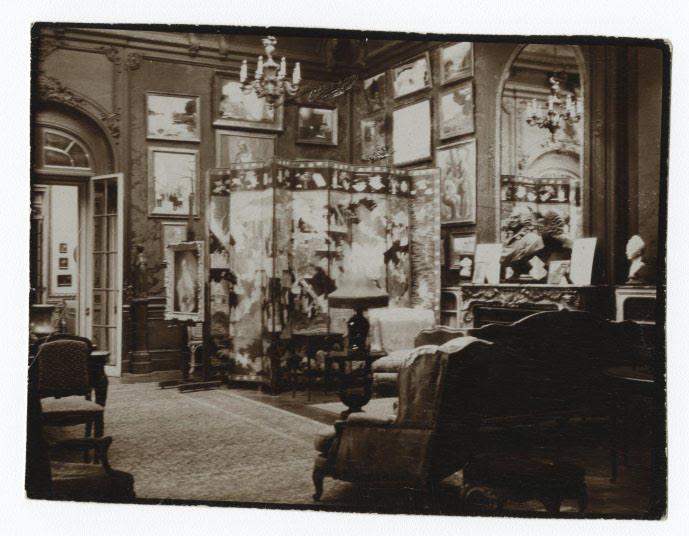

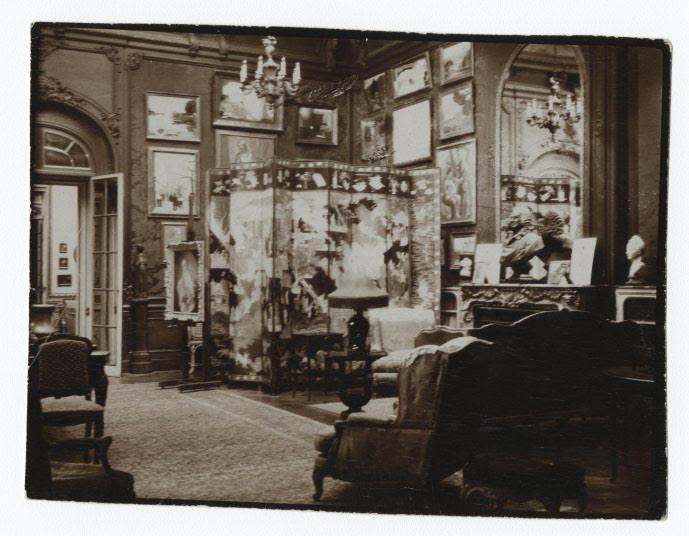

The heirs also included photographs showing the interior of the private mansion where he had lived from 1916 to 1933 (TGI, p. 8; see also for example picture 2). The three works claimed can be seen there, which "corroborates", according to the judges, "the reality of their possession by René Gimpel during this period", but this is not proof for the later period. Finally, his stock book mentions a painting for which a photograph negative is attached (Chapelle-sous-Crécy). However, the judges reject their claim: there is no doubt that Gimpel owned the artworks in the past, but this does not mean that he still had them during the War, nor that they were looted from him. For the judges, it is therefore not possible to identify the paintings with certainty, nor to put forward sufficiently convincing evidence to establish the existence of a spoliation.

The heirs then appealed, this time presenting the results of provenance research carried out by Margaux Dumas and Denise Vernerey-Laplace on the basis of the Gimpel family archives and available public records. Photographs might be found in private (family, private institutions) or public archives (State, museums) for instance. As such, one big difficulty lies in getting access to them, and the need of their opening for families and researchers.

Mrs. Dumas and Verney-Laplace found new elements, which were added to the case file: an envelope of photographs of the artworks "that he hoped to be able to negotiate for his survival"; "envelopes containing photographs and negatives of the works listed in the inventory" of René Gimpel (CA Paris, p.8), drawn up before his departure from Paris in July 1940. In addition to the photographic negative of the work La Chapelle-sous-Crécy, a print from this period also made it possible to identify the painting, which, according to the Court, was "perfectly recognisable". The judges identified the paintings on a photograph of the interior of the mansion, as well as the View of Cassis, which was also photographed for the inventory. The particularly significant provenance research work, which "was not available to the first judges", made it possible to "rectify previous errors and clarify various elements": the Court identified the artworks as having been the property of René Gimpel, including during the War, and ordered their restitution.

When reading these court rulings, photographs are not the only elements of proof. In fact, they must be combined with other information, such as inventories and personal details; any element that can help to give a context, an intention, and help to identify the work of art beyond the visual. Here we return to the basis of photographic analysis: contextualisation. Nevertheless, the presence or absence of photographs affects the interpretation of the other elements themselves (stock book, inventory, etc.). As such, they all together constitute a body of evidence, in which photographs as visual evidence are not of minor interest.

I would like to thank Margaux Dumas, for her input and indications relating to the photographic archives in this article. Margaux Dumas is Doctor in History and History of Art (TU Berlin / Université Paris-Cité). Her PhD thesis’s title is Silent witnesses. Looting of furnishings and artworks in occupied France and the implementation of restitution policies (1940-1950s). She is a post-doctoral researcher at the Labex “Les passés dans le présent”/IHTP/LESC (Paris), and she was one of the two provenance researchers in the Gimpel case.

Aliénor Brittmann is a doctoral candidate in law at ISP, Ecole Normale Supérieure de Paris-Saclay. She has received scholarships from the Académie française and the Italian government, as well as from the Ecole française de Rome. She is currently writing her PhD thesis thanks to a grant from the Fondation pour la mémoire de la Shoah (Paris). She was a Visiting Scholar at the Università degli Studi in Milan, Italy, where she obtained her diploma in photography from the Accademia (CFP) Bauer. Her research focuses on the legal uses of the past, the construction of victims as legal categories, the emergence of State liability, the links between history and trials, photography as a mode of evidence, the problems raised by human remains as cultural heritage, as well as museum collections from World War II and colonial contexts. Her PhD subject is Repairing the wrongs of history. Post-Shoah and post-colonisation in the French and Italian experiences of cultural property restitution since 1970. In her thesis, she analyses the way in which restitutions of cultural property removed during the Holocaust and colonisation are intended as attempts to repair - though impossible - these particular contexts of violence, which are today referred to as "wrongs of history". Her research begins in 1970 in order to work on post-historical events, both in France and in Italy; in other words, on the contemporary occurrence of cultural property disputes linked to these past conflicts.

This blog post is the first of a small series of articles that will be published in conjunction with the spring conference of the German Lost Art Foundation on the topic of “Provenance Research and Photography” on April 18th and 19th, 2024 in Leipzig.

Legal references

Tribunal de grande instance de Paris, jugement du 29 août 2019, n° RG 19/53387

Tribunal judiciaire de Paris, jugement du 27 janvier 2023, n° RG 22/54723

Conseil d’Etat, Assemblée générale, Section de l’intérieur, Avis sur un projet de loi relatif à la restitution ou la remise de certains biens culturels aux ayants droit de leurs propriétaires victimes de persécutions antisémites, jeudi 7 octobre 2021, n° 403728

Cour d’appel de Paris, Pole 2 - Chambre 1, arrêt du 30 septembre 2020, n° RG 19/18087

Loi n° 2022-218 du 21 février 2022 relative à la restitution ou la remise de certains biens culturels aux ayants droit de leurs propriétaires victimes de persécutions antisémites

Ordonnance n 45-770 du 21 avril 1945 portant deuxième application de l’ordonnance du 12 novembre 1943 sur la nullité des actes de spoliation accomplis par l’ennemi ou sous son contrôle et édictant la restitution aux victimes de ces actes de leurs biens qui ont fait l’objet d’actes de disposition

GOSSELIN, Béatrice, Sénat, Rapport fait au nom de la commission de la culture, de l’éducation et de la communication sur le projet de loi, adopté par l’Assemblée nationale après engagement de la procédure accélérée, relatif à la restitution ou la remise de certains biens culturels aux ayants droit de leurs propriétaires victimes de persécutions antisémites, n°469, 9 février 2022

COLBOC, Fabienne, Assemblée nationale, Rapport fait au nom de la commission des affaires culturelles et de l’éducation sur l projet de loi relatif à la restitution ou la remise de certains biens culturels aux ayants droit de leurs propriétaires victimes de persécutions antisémites, n°4911, 18 janvier 2022

Bibliographic references

Becker, Howard S., «Les photographies disent-elles la vérité ?», Ethnologie française, vol. 37, no. 1, 2007, pp. 33-42. The English translation in the text is my translation from this article in French.

Ministère de la culture, Dossier de presse – Annonce de la proposition de restitution du tableau de Gustav Klimt, Rosiers sous les arbres, Paris, 15 mars 2021

Mnookin, Jennifer L., "The Image of Truth: Photographic Evidence and the Power of Analogy", Yale Journal of Law & the Humanities, vol. 10, no. 1, Winter 1998, pp. 1-74, available on HeinOnline.

Photographs archival references

France, Archives du ministère des affaires étrangères, 209SUP/971 - De Gagnard à Gurlitt 1940-1950 - view no. 309, available online

ÖNB/Gerlach, ÖNB Bildarchiv und Grafiksammlung (POR) Bildarchiv und Grafiksammlung , Signatur: 465.840-D, Bildnis Serena Lederer in ihrer Wohnung in Wien, Bartensteingasse Nr. 8. An der Wand drei Gemälde von Gustav Klimt: "Wally", "Goldener Apfelbaum", und ihr eigenes Porträt "Bildnis Serena Lederer", available online